| Citrus Thrips in the Low Desert Testing ways to reduce their damage

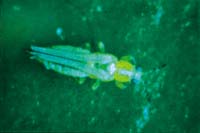

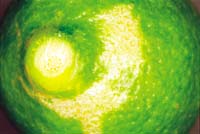

Citrus thrips don’t ruin a lemon’s pulp or juice, but they can make it look ugly enough for buyers to reject. For this reason, citrus thrips are considered the number one pest on citrus in Arizona, particularly in the low desert of Yuma County. "On large commercial trees, the immature thrips will feed on the rind of the fruit and cause scarring. As the fruit grows, it becomes more evident," says David Kerns, an IPM specialist at The University of Arizona’s Yuma Agricultural Center. Second instar thrips damage the rind by piercing and sucking juices from the surface cells; adult thrips don’t harm the crop. In addition to feeding on developing fruit, thrips also feed on young shoots. Although this does not reduce the yields of mature trees, it will often delay maturity of young non-bearing trees.

The citrus pulp on damaged fruit is still perfectly edible, but most people hold commercial fruit to a higher standard than the backyard variety and won’t buy it if it’s blemished. In particular, Asian countries prefer perfect fruit, especially Japan. Because a lot of Yuma-grown citrus is exported to Pacific Rim countries, appearance definitely counts. For the last three years, Kerns and a team of technicians and research laboratory aides, have been conducting several projects on lemons at the Agricultural Center and in commercial groves to develop management strategies for citrus thrips and thus reduce their damage. Along the way, one of their main goals is to reduce spraying in favor of monitoring and timing of controls. The research, sponsored by the Arizona Citrus Research Council, targets thrip population levels and fruit size; the guidelines for spraying certain pesticides and the preserving of predaceous mites; and pesticide efficacy. Fruit size and thrip population levels"We’re trying to determine the thrip population level we should treat," Kerns says. "When we sample the grove, at what point are there enough thrips that significant fruit scarring is a possibility?" The research began three years ago on untreated citrus located on the experiment station. Scientific literature maintains that citrus is susceptible to thrip damage beginning at petal fall and continuing through nearly 2 inches in size. Kerns wanted to investigate that aspect because nobody had studied it on lemons in the low desert. "We wanted to be able to tell at what point the growers could quit spraying," he explains. From petal fall to when fruit traditionally ceases to be susceptible to scarring, the flowering and fruiting season runs from March or early April until the first part of June. If growers are spraying fruit up to two inches, they’ll be spraying in June when citrus thrips are most difficult to control.

"The temperatures are high, the thrips are reproducing rapidly, and a lot of insecticide is needed to control them," Kerns says. "What we’ve found is that once the fruit reaches more than an inch in diameter, it doesn’t pay to treat it. Prior to that point a good threshold to use with immature thrips is about a ten percent infestation of fruit." The normal number of sprays is usually three in a light year, up to six or seven in a heavy year. That’s a major expense, and this method eliminates at least one spray at the end of the season. Kerns tested the thresholds on nearly 500 acres of commercial groves that belonged to cooperating growers. Because the spring of 1998 was fairly cool, the thrips did not build up the intense populations they had in previous years. Many growers followed the action threshold guidelines and sprayed only when the fruit size was quite small. "A lot of them really liked our fruit size information," Kerns says. "When the fruit reached more than an inch in diameter they pretty much held off treating. We had growers who sprayed only once or twice and some didn’t spray at all." Kerns and his team held workshops and field days, and presented information through the Citrus Newsletter, a monthly publication issued by the Yuma Agricultural Center. Insecticide use guidelines and predaceous mites

Another part of the study focused on which sprays should be used and under what circumstances. The researchers tested different products, including a new insecticide called Success, which does not kill the predaceous mites that feed on thrips. "When you spray for thrips with a harsh insecticide it takes out predaceous mites, parasitoids and other beneficials," Kerns says. "You’ll often get phytophagous mites and mealybugs as secondary outbreaks." Since the thrips arrive earlier on the scene than the beneficial insects and arachnids, growers have to figure out how to treat them without killing natural thrip enemies that can help later on. This next season Kerns will be looking more closely into the role the predaceous mites play in the system and how the right insecticides can be used in conjunction with them. Insect efficacy trials

In a related project the researchers are testing how long insecticides actually last on five acres of commercial citrus. There has been a lot of debate about this, and Kerns wants to find out whether or not the chemicals are really performing differently later in the season that at the beginning, or if it’s just that thrips populations are exploding so much more rapidly in June that the chemicals can’t keep up. "We’ve done a study using techniques similar to those developed by Joseph Morse at UC Riverside. We use tiny vacuum cleaners to collect immature thrips and then transfer them into cages containing insecticide treated lemon leaves, checking to see how long these insecticides will still provide commercially acceptable mortality," Kerns says. In all cases the goal is to reduce spraying and increase the populations of natural enemies, while still preserving fruit quality. |

|

Article written by Susan McGinley, ECAT, College

of Agriculture Researcher:

|