|

Borrowing from Mother Nature Water-short areas in the U.S. and around the world have turned to

reclaiming Another way, already established in Tucson, and under study here for nearly eight years, is soil aquifer treatment, or SAT. This method involves passing tertiary (filtered) water through a final filter of soil in an underground spreading facility. As the water moves through the soil, many of the harmful organisms die or adhere to the soil particles, allowing the now purified water to collect in the aquifer below. This method reduces the number and amount of chemical additives needed to purify the water. Charles Gerba, a soil scientist in the Department of Soil, Water and Environmental Science at The University of Arizona, is part of a cooperative team of university and water industry scientists who have worked to improve wastewater quality by imitating nature. "Nature has been in charge of purifying water since time began," Gerba says. "We need to understand and use her tricks. We're trying to take Mother Nature's job and do it faster." The critical issue is figuring out how water is purified in nature without additives. In Gerba's's case, his specialty is pathogens, including viruses and particularly the parasites Giardia and cryptosporidium. Gerba is searching for the best ways to identify and eliminate these pathogens from the city's water supply. "We try to understand what happens to them and how we can optimize nature's system for removing them," Gerba says. "Somehow, they filter through the soil and die with no additives. The best thing is that Mother Nature does this 24 hours a day: that's why I like natural systems." Gerba works with hydrologists Gray Wilson from the Department of Hydrology and Bob Arnold, from the Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering; and with hydrologists from Tucson Water who approached the university several years ago for help. Wilson focuses on removing nitrate compounds from water; Arnold strives to eliminate total organic compounds such as dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and total organic halides (TOX). "We're helping growth in the urban areas by helping communities deal with their waste," Gerba says. "We are using soil science and irrigation issues – the agricultural sciences – to help urban environments reuse wastewater."

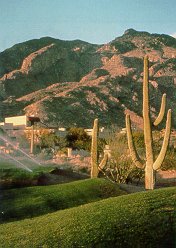

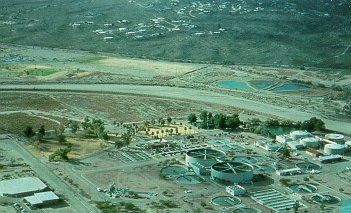

"We can ensure the water will be safe to drink after we determine how much more treatment will be necessary," Gerba said. As a parallel to the field studies, Gerba and his associates have compared lab purification trials to the SAT process used at the Sweetwater site. "We've done lab studies, adding chemicals and organisms to water to see how well they're being taken out. Then we go out into the field to see how it's happening there and how well we can predict those results based on what's happening in the lab," Gerba says. "We found a significant difference after the effluent passed through the soil, compared to the lab methods." The beauty of the SAT system lies in both its natural process and its low cost, according to Gerba. "I like going through natural systems because you lose the identity of it being wastewater," he says. "Mother Nature helps it lose its identity. We also like to use them because they're inexpensive." Yet Gerba stress es that water quality comes before low cost. "Our goal is always to be at the forefront in using the latest technology to try to find disease-causing organisms," he says. "Water quality is always based on the assurance that you've done all you can with the latest technology. At the same time, we are looking for low-cost methods to filter and test the water. Right now, tests for viruses can cost as much as $1000 each." The large number of publications generated from the project offer other water-short areas some references to follow in establishing or improving their own treatment facilities. Gerba cautions, however, that every area is different and may need a slightly different system. Cities and governments from Arizona, other states and other countries have contacted him for guidance. "The size of this project just gets bigger," Gerba says. "It has expanded in magnitude over the years. Since this work, we're now in a research arrangement with the City of Phoenix, and with Los Angeles and Orange County." The research has drawn international recognition and requests for advice from water-short areas around the world. Gerba has served as a consultant on SAT projects in Israel, Greece, Mexico and Australia. "Can we use this wastewater to irrigate playgrounds? That's the question Tucson Water asked ten years ago," Gerba says. "Tucson leads the nation in the intensive study of soil aquifer treatment. When people ask, 'is it safe,' we feel we've done the studies, we have the data to back it up, and we've been asking every critical question we can think of. I think we really have to give Tucson Water credit for that - for being willing to ask those critical questions ahead of time." The Study Location The heart of the system under study is the 14-acre Sweetwater Underground Storage and Recovery Facility in Tucson. Tucson Water recharges tertiary effluent from its Reclaimed Water Treatment Plant (RWTP) to the Sweetwater location for soil aquifer treatment.

The scientists wanted to determine the fate of nitrogen, selected organic compounds and pathogens as they passed through the soil aquifer treatment process. These substances pose the greatest harm to humans if the water is used for drinking water purposes. In California, both Los Angeles and Orange counties have used reclaimed water as drinking water for years, according to Gerba. Tucson may follow suit in a few more decades. Article Written by Susan McGinley, ECAT, College

of Agriculture Researcher:

|

wastewater

as a way to increase water supplies. Thus metropolitan areas run wastewater

through treatment plants to filter, clarify and disinfect it for reuse.

To be legally safe, even for irrigation, this water must test free

of toxic substances in dangerous concentrations. These include total

organic compounds, excess nitrogen, and disease-causing organisms

such as parasites, bacteria and viruses. One way to do this is to

filter the water and then treat it with chemicals to eliminate as

many of the dangerous constituents as possible.

wastewater

as a way to increase water supplies. Thus metropolitan areas run wastewater

through treatment plants to filter, clarify and disinfect it for reuse.

To be legally safe, even for irrigation, this water must test free

of toxic substances in dangerous concentrations. These include total

organic compounds, excess nitrogen, and disease-causing organisms

such as parasites, bacteria and viruses. One way to do this is to

filter the water and then treat it with chemicals to eliminate as

many of the dangerous constituents as possible. The

results of the monitoring at the Sweetwater Underground Storage and

Recovery Facility in Tucson (See Sidebar) showed the facility provided

safe, effective SAT for nonpotable water use. The researchers noted

a complete removal of enteroviruses as they passed through the 37-meter

soil vadose zone. Groundwater samples held no Giardia. The two organic

compounds were reduced by 92% (DOC) and 85% (TOX), and total nitrogen

leached out 47% during recharge.

The

results of the monitoring at the Sweetwater Underground Storage and

Recovery Facility in Tucson (See Sidebar) showed the facility provided

safe, effective SAT for nonpotable water use. The researchers noted

a complete removal of enteroviruses as they passed through the 37-meter

soil vadose zone. Groundwater samples held no Giardia. The two organic

compounds were reduced by 92% (DOC) and 85% (TOX), and total nitrogen

leached out 47% during recharge. The

researchers performed field-scale studies at the site during four

recharge seasons from 1989 through 1993, and they continue to perform

research at the facility today. They have monitored subsurface water

in the vadose zone — the unsaturated layer of soil above the water

table — and they sampled the groundwater underlying one of the basins.

The

researchers performed field-scale studies at the site during four

recharge seasons from 1989 through 1993, and they continue to perform

research at the facility today. They have monitored subsurface water

in the vadose zone — the unsaturated layer of soil above the water

table — and they sampled the groundwater underlying one of the basins.