|

Sharing Rivers, Sharing Opinions

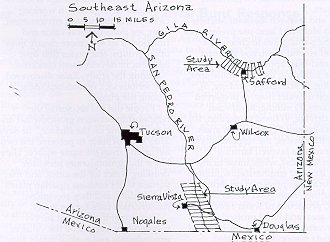

Homeowners, farmers, ranchers, real estate developers, natural resource managers, mining companies and other public and private groups value riparian areas for different reasons. Some groups want the areas to remain wild; others need the water for crops or grazing cattle. Still others see an attractive spot for housing or recreation. Managing a riparian area involves weighing these opinions and deciding which uses should predominate and why. Ervin Zube, a landscape architect in the School of Renewable Natural Resources at The University of Arizona, has spent 15 years researching land use patterns and landscape perceptions and attitudes in southern Arizona. He has looked at changes and trends in land-use from several angles, including ecologic and cultural. His study tools have included photo interpretation; literature reviews; comparisons with computer models; interviews; and both mail and telephone surveys. Gathered together, these data offer decision makers a tool to assist in land use planning and management. Since 1982, Zube has studied factors related to landscape changes in Arizona, and has found in earlier research that geological, ecological and climatic factors have been prominent agents of change in the past, whereas recent and frequently more rapid change now appears to be a result of cultural activities -- the activities of people -- mining, farming, ranching, introduction of non-native plants, and other human introductions to the land. “My career has focused on landscapes large and small,” Zube says. “What I’m interested in is what people value in their landscapes.” Riparian zones intrigue him because they are vital in Arizona for many conflicting needs. Urban and rural communities use the groundwater for drinking water and irrigation, while streamside plants and wildlife survive on both ground and surface water. Zube’s most recent work has focused on perceptions regarding two rivers, the Upper San Pedro near Sierra Vista in Cochise County, and the Upper Gila in Graham County near Safford (See map for study areas.) These are among the few remaining perennially flowing rivers in Arizona. Although both are considered desert riparian corridors, they differ in rates of adjacent human population growth, land use patterns, rates of flow, and other factors. The San Pedro River flows north from Sonora, Mexico into southern Arizona. The Upper San Pedro has received national recognition for its diversity of plants and animals, particularly its mammalian and avian species. In 1986, a 30-mile portion of the river was designated a National Riparian Conservation Area. The Upper San Pedro’s annual flow fluctuates between 9,589 and 26,278 acre feet of water, with a fairly consistent daily rate except for increases during the summer monsoons. Urban development has increased in the region because Sierra Vista (1994 population of 36,855) and Fort Huachuca are nearby. This development is moving steadily toward the conservation area less than five miles east of town. Cattle ranching is a major enterprise, and much of the land along the river is under public ownership. As the Upper San Pedro flows northward, it eventually joins the Upper Gila River. In contrast to the suburban character of the San Pedro River Valley where Sierra Vista lies, the town of Safford (1994 population of 8,020) and the region it occupies are considerably more rural. Crop agriculture predominates, and the Gila River flows at a volume that accommodates it: between 55,807 and 225,334 acre feet annually. Its most significant increases in flow occur both in the winter and in late summer. In contrast to the Sierra Vista area, much of the riparian land near Safford is under private ownership. Zube compared and contrasted the data for these two study areas, and then surveyed local residents and special interest groups for their perceptions. He and his research associates chose names at random from Sierra Vista and Safford area telephone books, and mailed questionnaires to potential respondents. Of those who returned their surveys, a smaller group was selected for personal, more in-depth telephone interviews. The survey population included a cross section of area residents and special interest groups (farmers, resource managers, realtors, environmentalists and local decision makers). In the mail surveys, respondents were asked to rate their preferred uses for lands adjacent to the river, and to choose the words that best described their opinion of each area. Categories included such descriptive terms as inviting vs. uninviting; beautiful vs. ugly; public vs. private; wet vs. dry; valuable vs. worthless; clean vs. dirty; productive vs. unproductive; unusual vs. common; and others. Zube and research assistant Michele Sheehan identified land-use preferences by asking participants to choose the most and second-most, and the least and second-least appropriate land uses from the following list:

Of all the choices, the respondents in the Safford area favored farming activities the most, while those in the Sierra Vista area emphasized wildlife and natural area preservation. Broken down further, strongest choices were farming, protection of water flow, wildlife area, and flood protection. Least favored uses for both Safford and Sierra Vista respondents included subdivisions, off-road vehicle driving, and mining. The responses ran along a continuum with adamant no-growth opinions at one end, and full, extensive use of riparian land at the other. “Many respondents were both anti-growth and anti-change, particularly the homeowners,” Zube says. They preferred to leave the natural beauty of the area intact. “The real estate developers advocated the most growth, not surprisingly. They were on the extreme utilization side. Fairly close to them were farmers and ranchers. On the opposite end were the resource managers who were for preservation.” These were the people who knew the most about the land--the Bureau of Land Management, Game and Fish, State Land Department, the Forest Service, and nonprofit conservation groups such as Audubon. “While the conservation side favored setting aside the riparian areas as wildlife refuges, the other side felt there was adequate planning there, with room for more growth,” Zube says. “The general public fell somewhere in the middle, but leaned more strongly toward conservation than use.” Interestingly enough, the resource managers perceived the riparian areas to be less inviting, beautiful and useful and more private and unnatural than any other group, according to Zube’s report. (In other words, these areas didn’t meet their standards for what a pristine wildlife habitat should be.) At the same time, they judged it more valuable, unusual and wetter, and perceived it as having more wildlife than the other groups had indicated. This pattern of responses may result from the greater knowledge resource managers have gained in working closely with the natural environment. They see the ecological value and function of an area more clearly than other groups, and prefer that over aesthetic or development concerns. During the study, Zube discovered one serious lack of understanding among the public. “People did not recognize the relationship between groundwater and water running on the surface,” he says. They did not seem to perceive the two as coming from the same source. They knew that groundwater provides drinking water for the cities, and that surface water sustains riparian plants and wildlife, and they recognized conservation uses for the water. “In spite of the fact that survey respondents recognized the value of groundwater and surface water, they simultaneously supported practices that reduce groundwater and therefore surface water,” Zube explains. Misperceptions like these can lead communities to continue aggressive development without realizing the full consequences until it is too late. Zube’s research therefore not only targets the positions different groups maintain regarding riparian areas, it also points out the need for education. Opinions and perceptions are valuable, but good planning relies on an understanding of the facts regarding an area. By finding out how people perceive a situation, Zube’s survey pointed out a need for public education regarding the way a riparian area works. “Perhaps this is a role resource managers must play, of educating the public about threats to riparian areas from uncontrolled growth and indiscriminate land use practices,” Zube maintained in a 1987 report. Because many riparian areas now support recreational activities, “resource managers have now become managers of people as well as resources.” He believes that to preserve the characteristics people most value in these riparian areas, restraints must be placed on growth and development. “One of the major challenges to planning will be directing growth while preserving and protecting as many of the valued landscape attributes as possible, attributes that attracted people to these areas in the first place,” Zube says. Riparian Zones “Riparian areas are the single most important landscapes in the state because they are the primary sources of water in the desert — both surface and groundwater,” Zube wrote in a 1989 report. “They are also the places where one usually finds the best alluvial soils, the easiest routes for travel, and the greatest floral and faunal diversity. It is not surprising, therefore, that they are valued for nearly every land use activity that occurs in rural areas, ranging from agriculture and mining, to sites for towns, and to recreation places and wildlife habitat.” With all of these choices available, the difficulty lies in blending together a community’s chosen land use activities. Fragile riparian corridors can only support the activities that allow the rivers to survive and nourish the land. Article Written by Susan McGinley, ECAT, College

of Agriculture Researcher:

|

As

Arizona’s riparian areas continue to shrink, and in some places, disappear

altogether, the few that remain must serve conflicting multiple uses.

These rivers and the lands surrounding them can supply irrigation

and drinking water, fertile soils, scenic views, forage plants, and

wildlife habitats.

As

Arizona’s riparian areas continue to shrink, and in some places, disappear

altogether, the few that remain must serve conflicting multiple uses.

These rivers and the lands surrounding them can supply irrigation

and drinking water, fertile soils, scenic views, forage plants, and

wildlife habitats.  Zube

defines riparian areas as the narrow strip of moist soils adjoining

either side of a stream or river. This area includes most of the visible

vegetation and the large trees, such as cottonwoods, that usually

line a natural waterway. Because riparian zones comprise less than

300,000 acres, or 0.4% of the state, fierce debate often ensues over

their most appropriate uses.

Zube

defines riparian areas as the narrow strip of moist soils adjoining

either side of a stream or river. This area includes most of the visible

vegetation and the large trees, such as cottonwoods, that usually

line a natural waterway. Because riparian zones comprise less than

300,000 acres, or 0.4% of the state, fierce debate often ensues over

their most appropriate uses.