Climate Viticulture Newsletter - 2020 October

< Back to Climate Viticulture Newsletter

Hello, everyone!

This is the 2020 October issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter – a quick look at some timely climate topics relevant to winegrape growing in Arizona and New Mexico.

A Recap of September Temperature and Precipitation

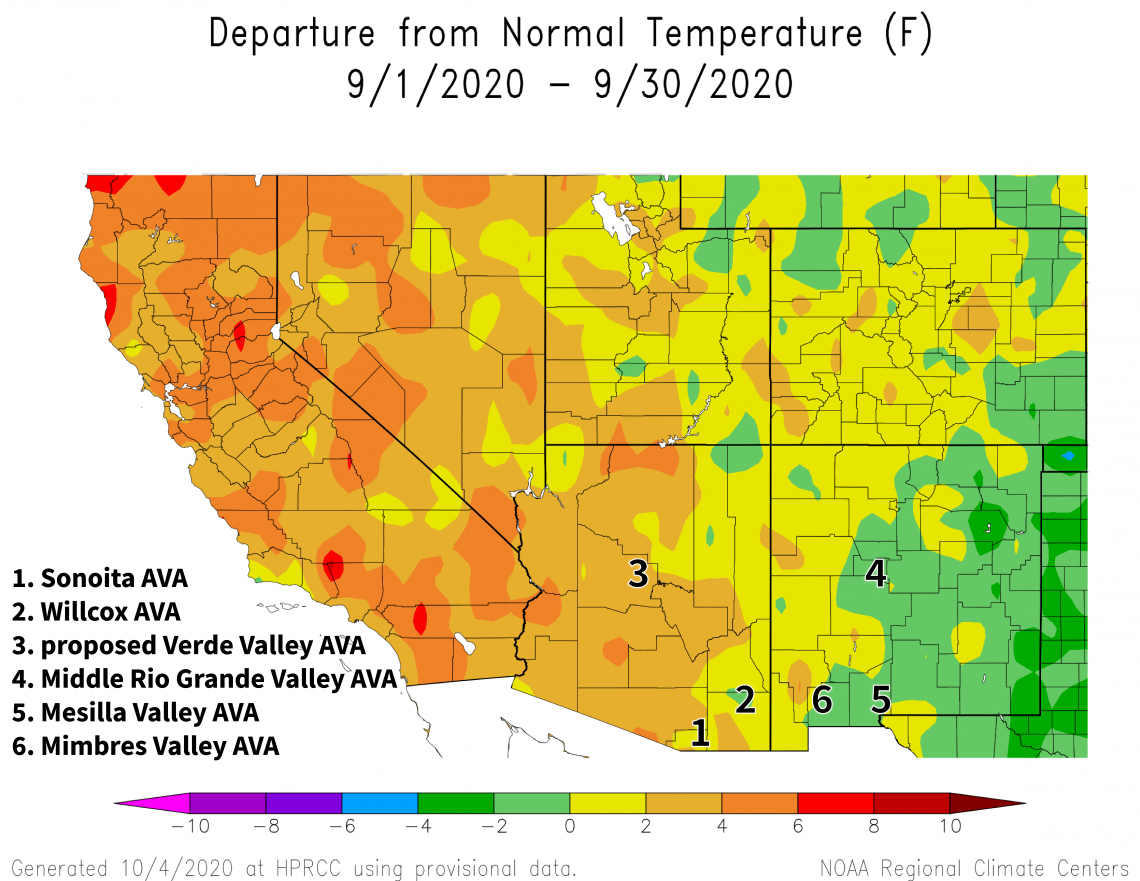

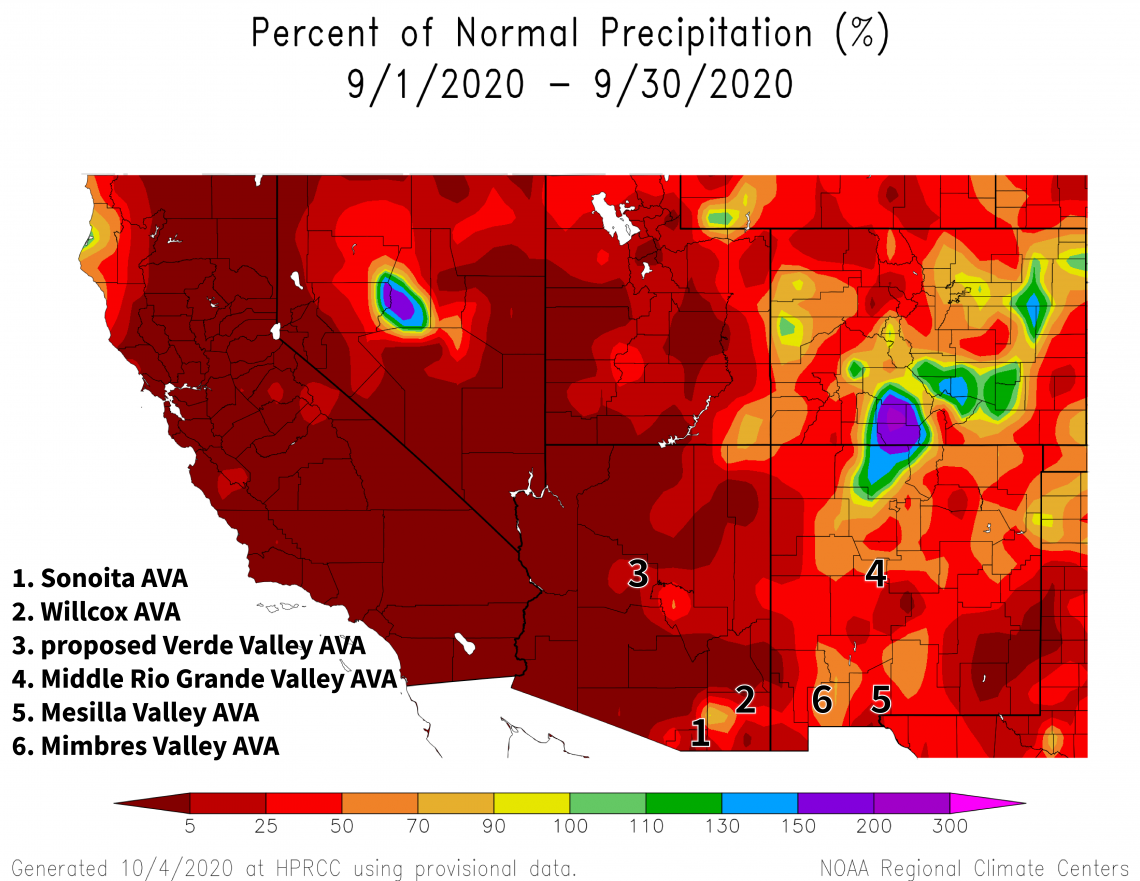

A gradient from above- to near-normal temperatures covered the region from west to east last month. Temperatures across most of the western two-thirds of Arizona were 2°F to 4°F warmer than the 1981-2010 September normal (light orange areas on map), and within 2°F of normal for the rest of the region (yellow and green areas on map). Buried in these monthly values was the long-awaited exit of temperatures above 95°F and entrance of temperatures below 65°F for relatively warmer growing areas, something we’ve been looking at during the ripening period this year. For comparison, temperatures in September 2019 were within 2°F of normal for southern and western Arizona and 2°F to 6°F above normal for much of the rest of the region.

Another month, another round of lacking rainfall. Precipitation totals for September were below 50% of normal for almost all of Arizona and much of New Mexico (red areas on map). This is quite a contrast from last year for the southern half of Arizona and the ‘bootheel’ area of New Mexico, when monthly totals were more than 150% of normal due to moisture from Hurricane Lorena. Most of the rest of the region, however, saw below-average amounts in September 2019.

Although irrigated vineyards are the norm in the region, the record hot and dry summer this year may nonetheless have brought questions of water stress to mind. Last month, we mentioned leaf shedding as a strategy vines use under relatively severe conditions to shield perennial parts like trunks and cordons from hydraulic failure. Apparently, severe conditions may also be too much for the remaining leaves, such that they can no longer reach normal levels of transpiration even if more optimal soil moisture returns. New leaves will be needed for normal transpiration at this point.

The Outlook for October Temperature and Precipitation

With harvest either done or close to wrapping up, post-harvest management of irrigation and fertilizer and a chance for vines to fix and store carbon and take up nutrients are again central features of the coming month. These aspects might take on extra importance this year if heat or water stress limited vine photosynthesis and carbohydrate production during the past few months. The record hot and dry conditions this summer already are seen as a factor that lowered 2020 yields in both Santa Cruz and Cochise counties in southeastern Arizona.

There is a moderate increase in chances for above-average temperatures across all of Arizona and New Mexico (dark orange areas on map). As a comparison, temperatures in October last year were near or below normal for much of the region.

2020-oct-temp-outlook-noaa-cpc.gif

A slight increase in chances for below-normal precipitation exists for Arizona (tan areas on map), while a moderate increase in chances for below-normal precipitation exists for New Mexico (brown area on map). Monthly precipitation totals in October 2019 were below 50% of normal for much of the region except southeastern New Mexico, where remnants of tropical storm Norda led to totals of more than 150% of normal.

2020-oct-prcp-outlook-noaa-cpc.gif

First Fall Freeze

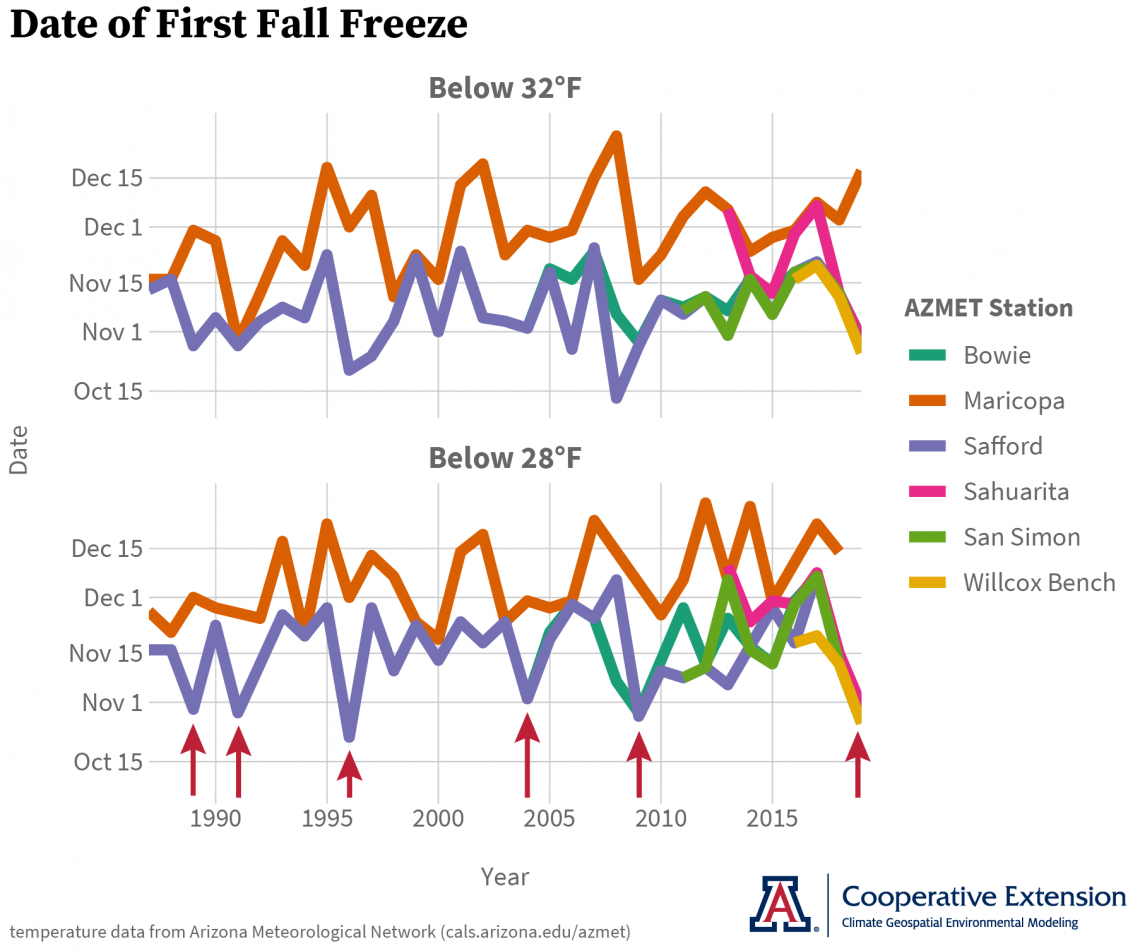

Based on the 1981-2010 normals, we would expect the first fall freeze to happen by the end of this month for relatively cooler growing areas in the region. Dates of the first fall freeze do not typically occur until the first half of November for relatively warmer growing areas, although cold spots with dates in the second half of October do appear in places like the Sonoita, Willcox, and proposed Verde Valley AVAs due to the influence of topography.

Last year, many locations in these warmer areas recorded the first fall freeze at the end of October, some with several hours below 28°F and minimum temperatures as low as 20°F. Based on records from Arizona Meteorological (AZMET) Network stations in southeastern Arizona, it looks like the last late-October or early-November hard freeze occurred in 2009 (red vertical arrow on graph). Prior to that, we see them in 2004, 1996, 1991, and 1989. So, first fall freeze events do happen near Halloween in and around the Willcox AVA, as well as the Sonoita and proposed Verde Valley AVAs, but not very often.

Depending on vine phenology and vineyard location, timing of the first fall freeze last year could have been prior to plants reaching cold-hardiness levels – through, for example, tissue dehydration – needed to withstand such temperatures. Any resulting damage to latent buds and their inflorescence primordia would have put a dent in yields this year, perhaps in combination with the record heat this summer.

azmet-first-fall-freeze-apga2020-2020-07-28-logo.png

La Niña 2020-2021

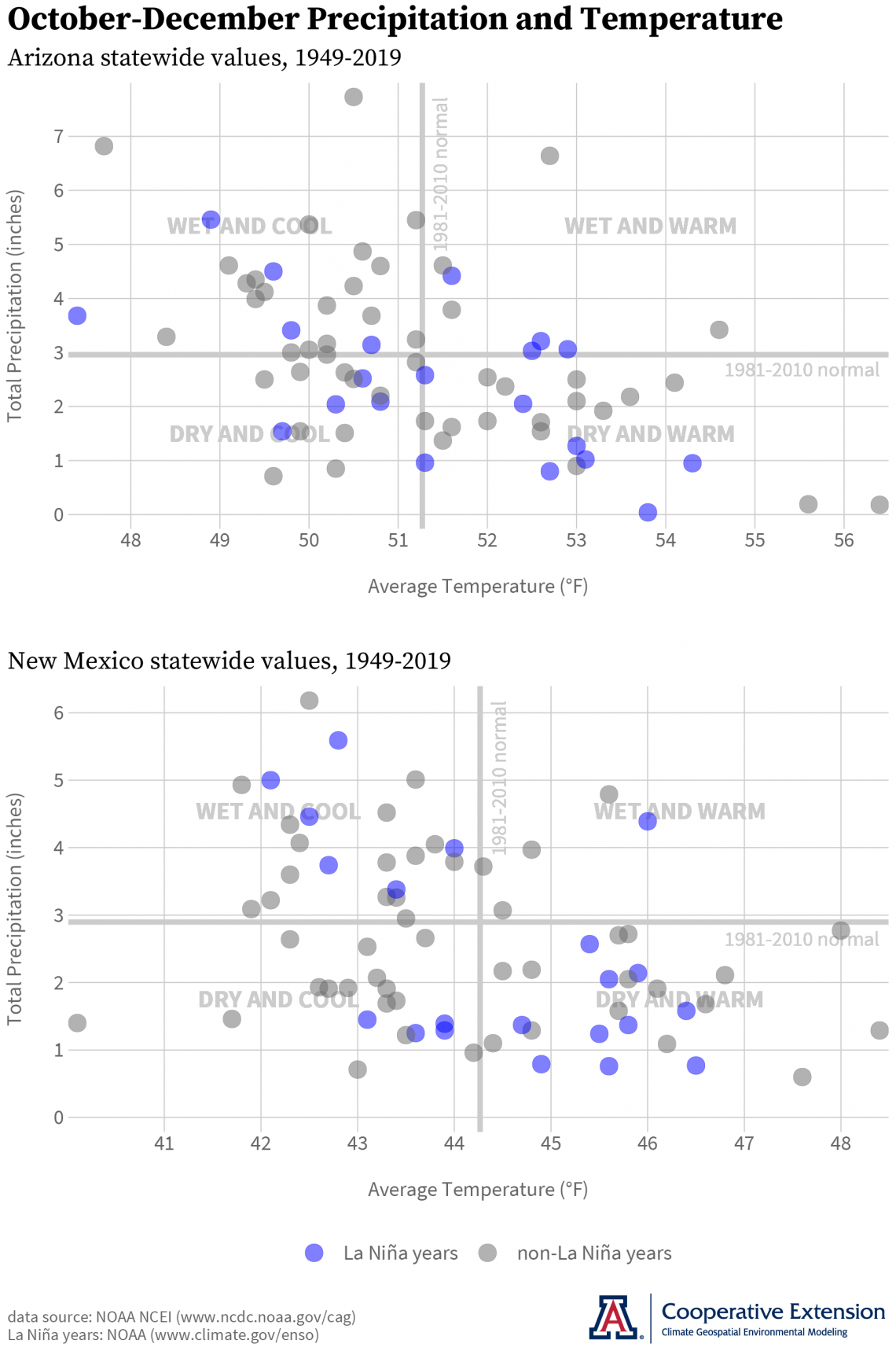

La Niña conditions have developed in the tropical Pacific Ocean and current forecasts show that a weak to moderate event is very possible this fall and winter. Changes brought about by a La Niña event can shift the storm track northward such that it passes through the Southwest less often. This can lead to fewer storms passing through the region and result in fewer chances for cool-season precipitation.

Since 1949, there have been 21 La Niña events. Total precipitation for the October-December period was below the 1981-2010 normal for 12 of these in Arizona (blue dots below thick gray line in upper graph) and for 14 of these in New Mexico (blue dots below thick gray horizontal line in lower graph). For temperatures averaged over this three-month period, below- and above-normal conditions are roughly equal in number (blue dots to the left and right of thick gray vertical line in both graphs). La Niña events with below-normal precipitation often have occurred with above-normal temperatures (blue dots in the ‘Dry and Warm’ quadrant of both graphs), a general direction that the October outlook above seems to have us going.

az-nm-state-tavg-prcp-lanina-cvn-2020-10-01.png

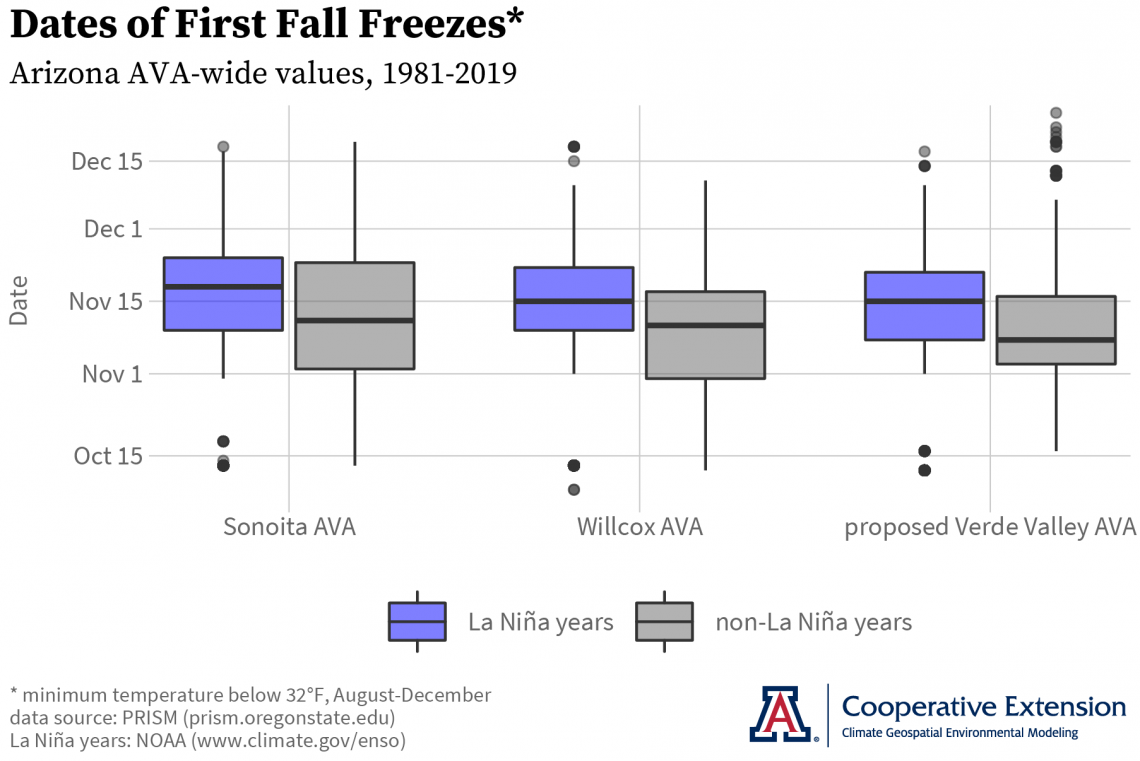

Dates of First Fall Freezes during La Niña Events

Do the present La Niña conditions provide any insight as to when the first fall freeze might occur this year and prompt vine dormancy? During the previous 12 La Niña events since 1981 (blue boxes on graph), for example, median dates of the first fall freeze were five to eight days later than those during non-La Niña years (gray boxes on graph) for the Sonoita, Willcox, and proposed Verde Valley AVAs.1 This apparent tendency for later first fall freeze dates during La Niña events is consistent with the scenario of a northward-shifted storm track that reduces the number of storms – and their associated colder air – passing through the region this time of year.

1 Horizontal black lines within rectangles of this boxplot represent the median, or 50th percentile, of first fall freeze dates. Upper and lower rectangle edges are the upper quartile, or 75th percentile, and lower quartile, or 25th percentile, respectively. Vertical lines above and below rectangles depict the range of remaining values in the distribution of first fall freeze dates except for outliers, which are depicted as dots.

az-avas-fff-time-series-la-nina-2020-10-02.png

Given the current situation regarding COVID-19, we currently are postponing the Growing Season in Review workshops for 2020.

Isaac Mpanga, Area Associate Agent with Cooperative Extension in the Verde Valley, is leading a monthly series of remote meetings for commercial horticulture and small-scale farmers to share science-based information on topics like pests, diseases, marketing, and food safety. The goal is to help improve farm productivity, profitability, sustainability, and food security. Please email yavapaipres@cals.arizona.edu to register. The next meeting is October 14.

For those of you in southeastern Arizona, Cooperative Extension manages an email listserv in coordination with the Tucson forecast office of the National Weather Service to provide information in the days leading up to agriculturally important events, like incoming moisture from tropical cyclones and the first fall freeze. Please contact us if you'd like to sign up.

Please feel free to give us feedback on this issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter, suggestions on what to include more or less often, and ideas for new topics.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Please contact us to subscribe.

Have a wonderful October!

With support from: