Life In Seemingly Lifeless Conditions

Desert Crusts

Life can flourish even under the harshest of desert conditions. At first glance almost devoid of life, deserts where soil-surface temperatures exceed 65°C (150°F) during daylight hours only to plummet to near-freezing at night, and where the soil may be so dessicating that plants allow their roots to die back to avoid water loss through root exudates, may harbor a wide array of some of the toughest organisms on Earth.

Desert crusts are composed of a community of drought-resistant and heat-tolerant microbiota (algae, cyanobacteria, fungi, lichens, and mosses) held together by sticky polysaccharide secretions. In the Sonoran Desert, the brown and dessicated crust easily escapes notice until rain falls, after which the photosynthetic members of the community green within hours. Under harsher conditions, these organisms avoid the searing heat by growing under the surface, protected in a unique microhabitat.

|

|

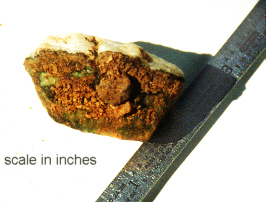

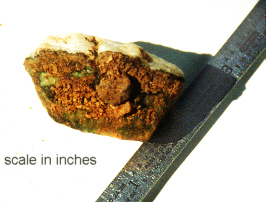

Calcareous or siliceous stones (e.g., quartz and chalcedony) not only reduce soil temperature and preserve moisture in the soil beneath them, but also transmit visible light to depths as much as 5 cm (2 inches), thus supporting photosynthesis below ground and under complete protection from the macroenvironment. |

Cyanobacteria are normally the commonest life form of the hot deserts. Some species fix atmospheric nitrogen into the soil, while others bind soil particles, thus reducing erosion. Some bacterial colonies derive energy from soil sulfur compounds. Fungal species may parasitize the algae and cyanobacteria or unite with them to form lichens. Moss species weave the whole community together. In the sub-stone microhabitats roam protozoa, nematodes, mites, and other arthropods, creating a microcosm where grazers and predators feed on bacteria, algae, fungi, detritus, or each other.

Desert Varnish

Even exposed, porous desert rocks can support life. Crustose lichens are the most conspicuous species found on hot desert surfaces. These lichens can endure many months of dehydration, and can continue photosynthesizing at temperatures where other plants would shut down. But even these lichens have a limit, and when their threshold is exceeded, they are replaced by bacteria.

|

|

The dark, often shiny surfaces of sun-baked porous rock are actually large colonies of bacteria, and are colloquially referred to as "desert varnish." The colonies obtain energy from inorganic and organic substances. They adsorb submicroscopic particles of wind-borne clay particles to their cellular surfaces to form a thin layer that protects them from direct sunlight. Over time (perhaps over hundreds of thousands of years), the outward-growing bacterial colony oxidizes minute quantities of wind-blown manganese and iron particles, which then combine with the clay minerals to form the well-known tough coating of dark manganese oxide or reddish iron oxide. |

Interstitial Species

Algal colonies may exist in places where neither lichen nor bacteria have been able to gain a foothold. Completely hidden within the matrix of the sedimentary rock itself, a zone of algal growth occurs between 1.5 and 3.7 mm beneath the surface. Like their rock-surface counterparts, these species may estivate for months, enduring periods of extreme dessication, flushing into metabolic activity following rainfall.

Cold deserts, such as Antarctica's dry valleys, also harbor such interstitial species.

References

Marchand, P., 1998. Windows on the desert floor, Natural History 107:4, 28-31.

Parfit, M., 1998. Timeless valleys of the Antarctic Desert, National Geographic (October), 120-135.

Back

Back