Climate Viticulture Newsletter - 2021 May

< Back to Climate Viticulture Newsletter

Hello, everyone!

This is the May 2021 issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter – a quick look at some timely climate topics relevant to winegrape growing in Arizona and New Mexico.

A Recap of April Temperature and Precipitation

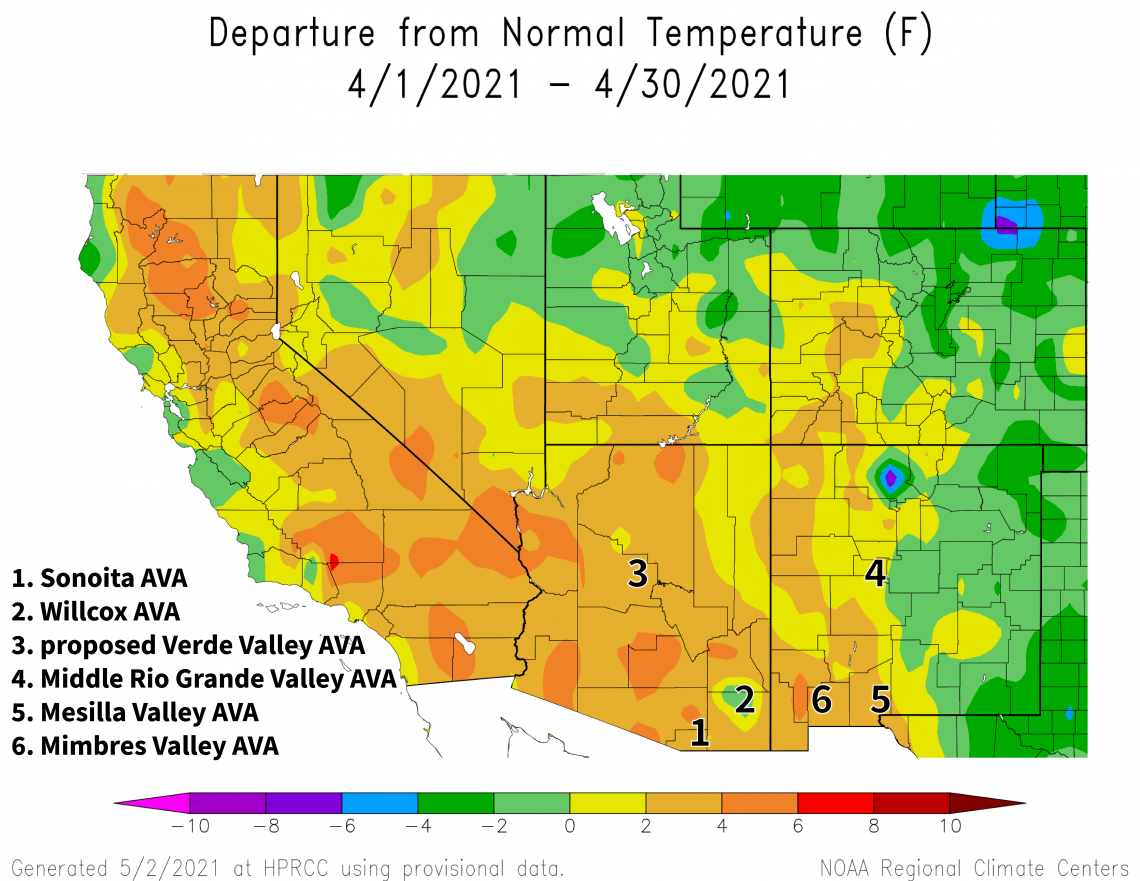

In general, conditions became relatively cooler as one went east. Temperatures last month were 2 to 4 °F above the 1981-2010 normal for almost all of western and central Arizona and parts of western New Mexico (light orange area on map). This warmth gradually gave way to temperatures within 2 °F of normal in far eastern Arizona and most of New Mexico (yellow and light green areas on map), with some parts of far eastern New Mexico 2 to 4 °F below normal (dark green areas on map). Broadly speaking, temperatures this year look to have been warmer in Arizona and cooler in New Mexico than those of April last year.

Temperatures last month kept chill and heat accumulation – and their influences on the timing of budbreak – somewhat similar to that of the past two years. We recap some of the differences in a last look at dormancy and the start of this growing season below.

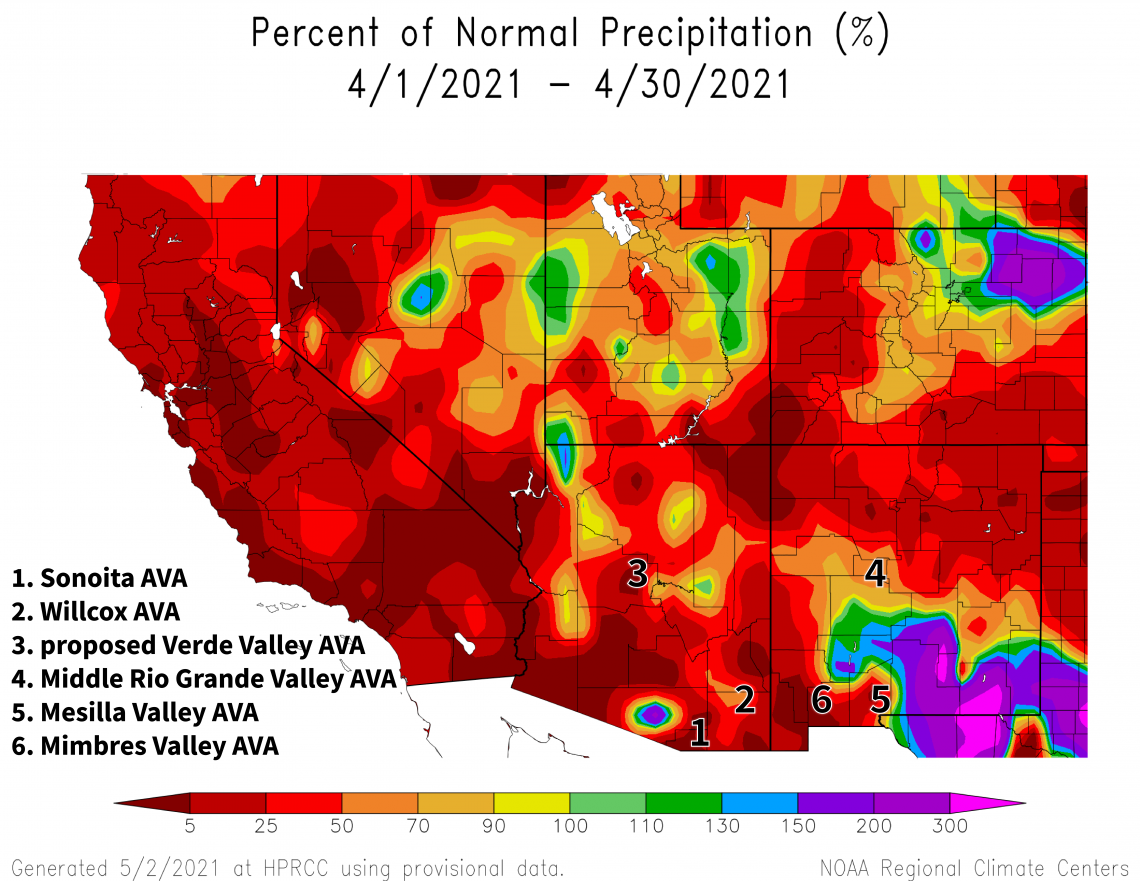

Monthly totals less than 50% of the 1981-2010 normal covered most of Arizona as well as far western and northern New Mexico (red areas on map). In contrast, much of southeastern New Mexico measured amounts greater than 150% of normal (purple and magenta areas on map). For many places, the relative lack of precipitation this year repeats what was experienced in April 2020.

Although we all know that April doesn’t fall during one of the wetter times of the year, precipitation last month nonetheless didn’t do much to help the ongoing regional drought conditions. No matter how one slices it – the past few months, the past year, the past few years – amounts have been below normal. Without enough precipitation to help flush salts past upper root zones, soil salinity may become an issue, particularly if the groundwater used for irrigation is saline.

View more NOAA ACIS climate maps

The Outlook for May Temperature and Precipitation

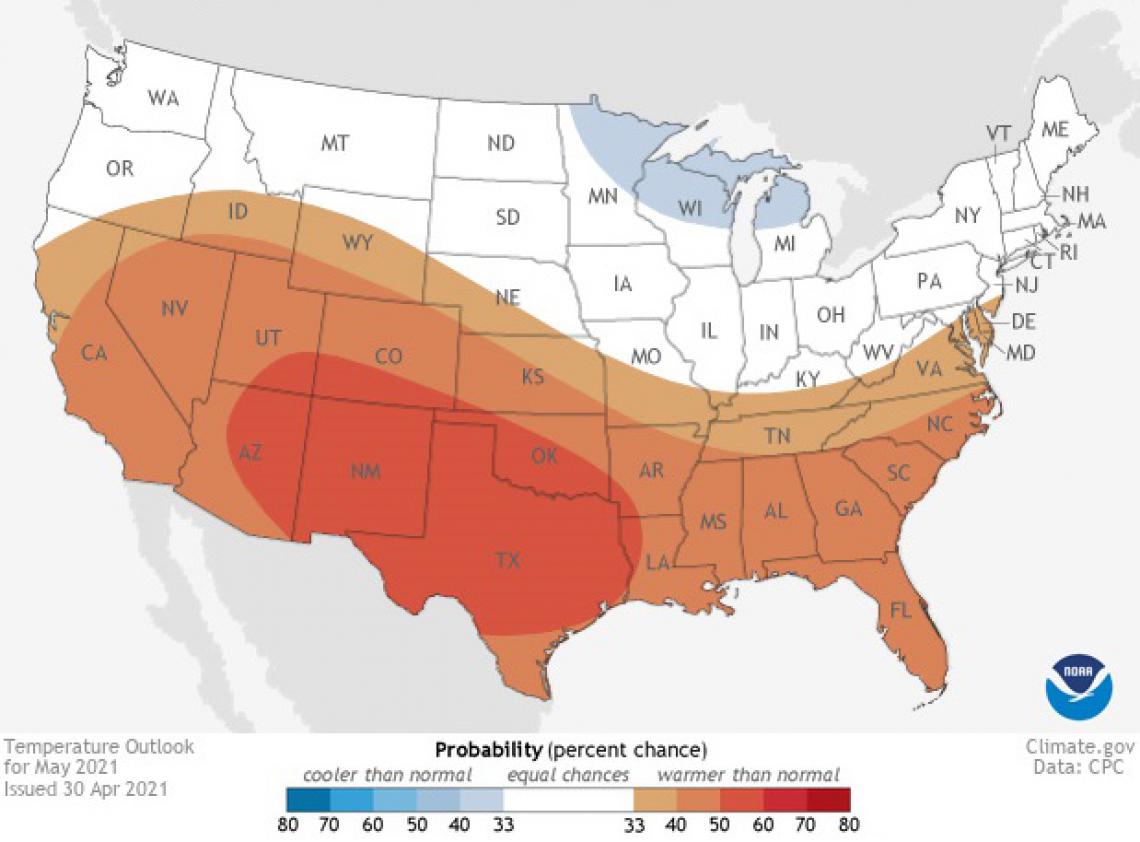

Moderate chances for above-normal temperatures extend from all of New Mexico to much of eastern and northern Arizona (dark orange area on map). Slight chances for above-normal temperatures exist for extreme southern and western Arizona (orange area on map). For reference, monthly temperatures in May last year were 2 to 6 °F above the 1981-2010 normal for almost all of Arizona and New Mexico.

2021-may-temp-outlook-noaa-cpc.jpg

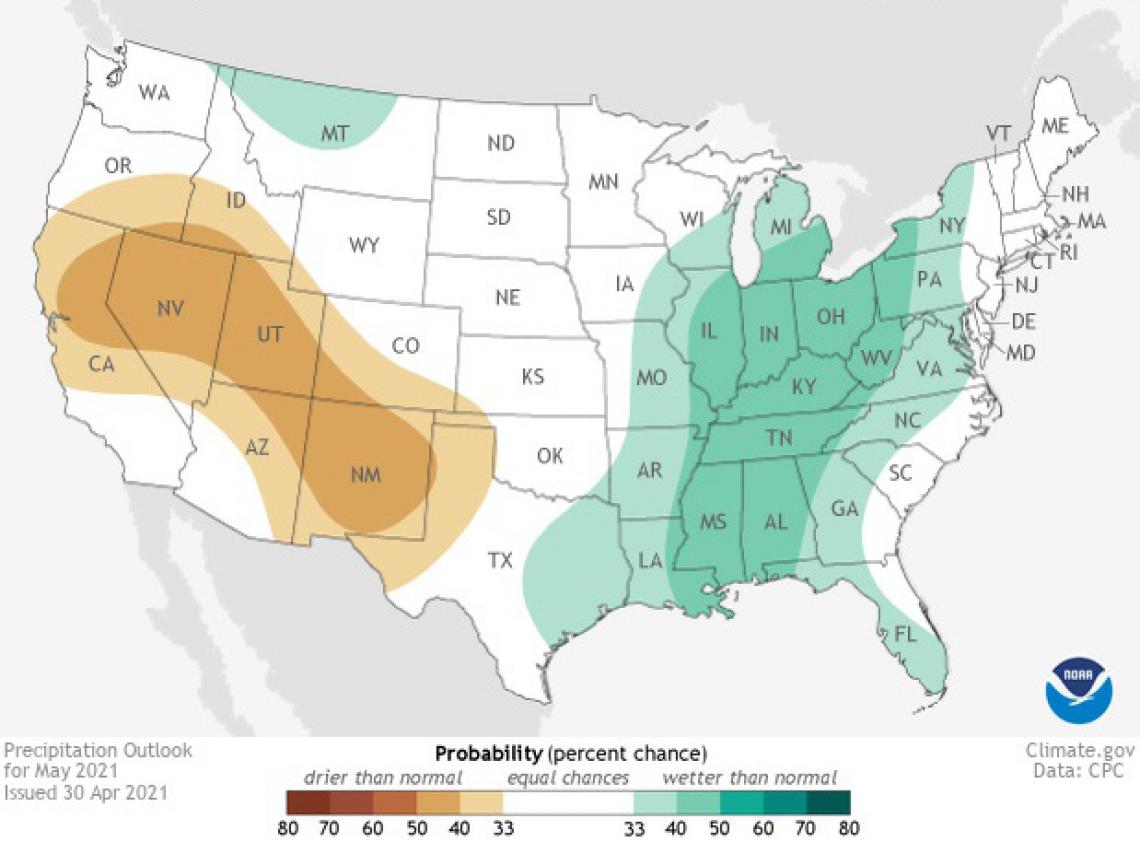

A slight increase in chances for below-normal precipitation also extends from all of New Mexico to much of eastern and northern Arizona (light and dark tan areas on map). Equal chances for below-, near-, or above-normal precipitation exist for the southwestern half of the Grand Canyon state (white area on map). Looking back at May 2020, monthly precipitation totals were less than 50% of normal for almost the entire region.

The outlook for this month points more towards the record-territory hot and dry conditions in May 2020 than the cool and wet ones in May 2019. That being so, field notes from the vineyard this time last year may be the better reference. In terms of temperature, the increased odds for warmer-than-normal conditions may also mean increased odds for shorter interphases – the time between growth stages – during this early part of the growing season. We take a look below at some of the reasons why this might matter. In terms of precipitation, higher chances for drier-than-normal conditions make it look like May will be another month that doesn’t do much to help the ongoing regional drought conditions.

Read more about the May 2021 temperature and precipitation outlook

2021-may-prcp-outlook-noaa-cpc.jpg

Vine Dormancy and the Start of the Growing Season

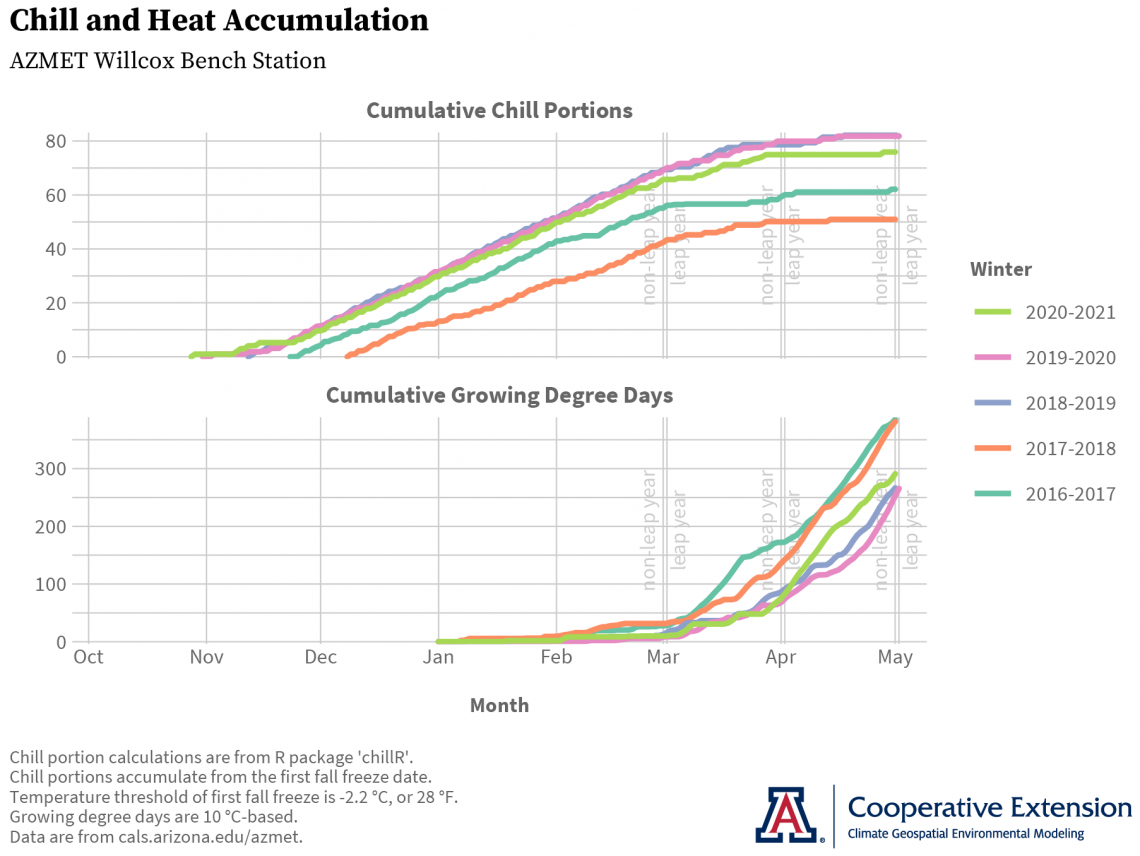

Now that budbreak is in the rear-view mirror for perhaps all but the coolest growing areas in the region, we’ll take one last look at conditions influencing the start of the growing season and wrap up our view of vine dormancy for this year. With temperatures last month, values of both cumulative chill portions and cumulative growing degree days for winter 2020-2021 (green line on graphs) ended up between those during winters 2019-2020 and 2018-2019 (pink and blue lines) and winters 2017-2018 and 2016-2017 (orange and aqua lines) at the AZMET Willcox Bench station in the south-central part of the Willcox AVA. Based on degree-day calculations from the National Phenology Network, heat accumulations for other warm-climate growing areas in Arizona also are above those at this time last year, whereas accumulations for such areas in New Mexico are similar.

From what we’ve heard so far, budbreak in Arizona this year is slightly later than what it was last year. From our perspective, this is good news as it is consistent with what we were anticipating at the beginning of April. One factor leading us to expect slightly later budbreak dates in 2021 was the potential for lower soil moisture levels due to record-low precipitation amounts over the past 12 months. Low soil moisture can delay or reduce bud rehydration, swelling, and weeping, as well as push back budbreak dates. Another factor was slightly less chill accumulation this year relative to the past two. Due to deacclimation kinetics, this can translate to a slightly lower rate at which dormant buds deacclimate and a slightly longer time over which they lose cold hardiness. Although we don’t know the exact roles each of these factors played, we’re happy that we seem to be on the right track in understanding and predicting budbreak in Southwest.

If you haven’t already, please reach out and let us know how budbreak timing was in your vineyard this year.

Heat Accumulation during the Growing Season

With budbreak now in the rear-view mirror for many if not all vineyards, we’ll also take a first look at how heat has accumulated since the start of the growing season. The topic has been getting increasing attention globally, with studies showing links between warmer temperatures and shorter interphases – the time between growth stages – in the early part of the growing season. Since it has been well known for many years that higher temperatures – up to a certain point – drive higher rates of cell division, photosynthesis, respiration, and growth in vines, you’d be right in thinking that compression of early-season phenology wasn’t the driving issue for that research. What actually motivated these studies is the growing number of vintages with earlier harvest dates, on the order of weeks in some cases.

Researchers have worked backwards from harvest to see what could be driving its advancement on the calendar. Is ripening occurring at faster rates? Or, is veraison – the start of the ripening period – occurring earlier? Respective answers generally have been ‘no’ and ‘yes’. That being so, what then is causing earlier veraison dates? The answer to this is a mix of two things: growth stages prior to veraison, like budbreak and flowering, happening earlier in the year; and shorter times between such stages. Exactly how much of these going into the mix depends on when warmer temperatures occur, which may or may not be the same from year to year.

Turning things back around, we can see that timing of phenological stages early in the growing season can affect timing of when – and, as an important consequence, the conditions under which – grapes ripen. With earlier harvest dates, additional studies point out that grapes often are ripening under warmer temperatures, which, due to the many effects that temperature has on fruit composition, has resulted in higher sugar concentrations, less acidity, higher pH, and changes in aromatic and phenolic compounds.

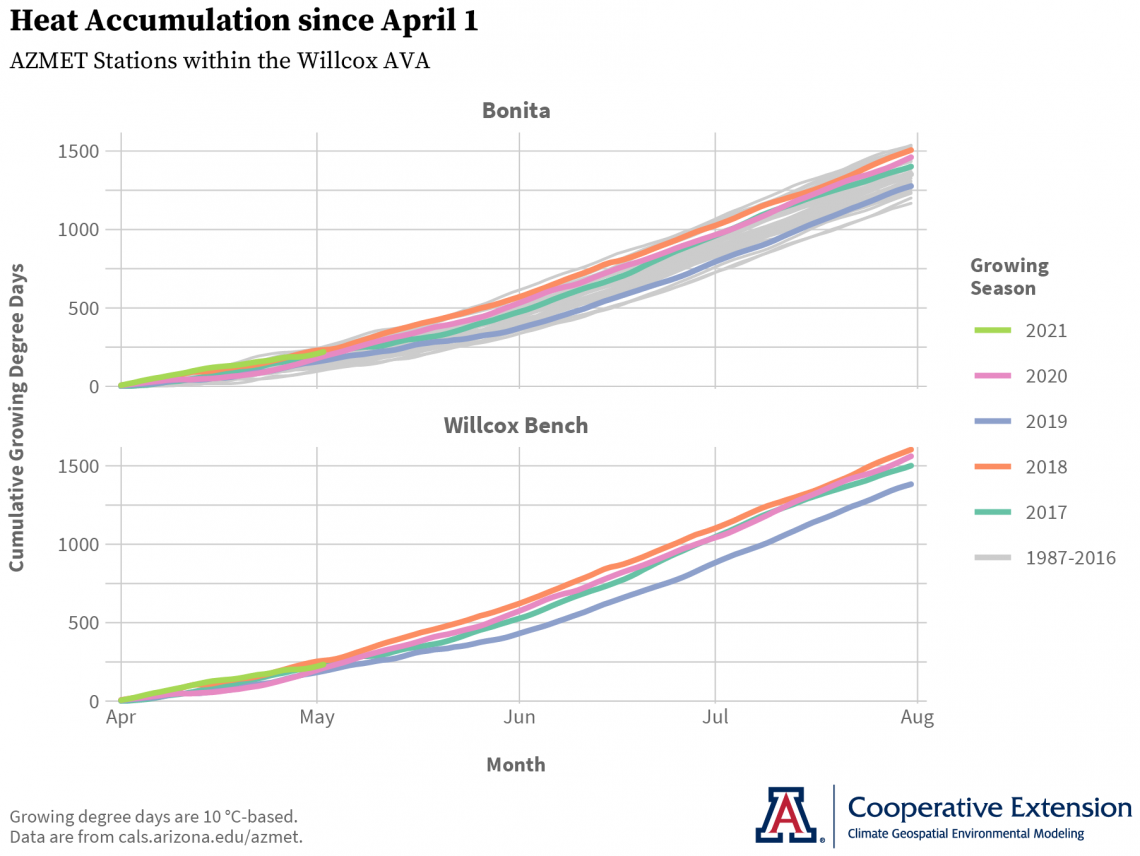

We may not yet know of any such fruit composition issues for the Southwest, but we nonetheless can monitor temperature at this time of year for insight on potential changes in vine phenology that might affect near-term planning of vineyard activities. Starting on April 1, heat accumulation so far this growing season at the AZMET Willcox Bench station (green line on lower graph) is similar to values observed over the previous four (pink, blue, orange, and aqua lines on lower graph). For even more historical perspective, we’ve included data from the AZMET Bonita station in the northern part of the Willcox AVA (upper graph). Heat accumulation there is very similar to that at Willcox Bench for this and the previous four growing seasons. Stretching back to 1987, the longer data record at Bonita shows that these recent years, except for 2019, are characterized by some of the highest accumulations early in the growing season (gray lines on upper graph).

Even though budbreak looks to have occurred slightly later this year relative to the past few, it may not translate to a relatively late veraison date if the anticipated above-normal temperatures this month get their say and hasten the occurrence of early-season growth stages.

It’s no surprise that regional drought conditions aren’t helping the wildland fire season in the Southwest. There is an above-normal potential this month for significant wildland fires for all of Arizona and New Mexico.

Undergraduate students in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at the University of Arizona are looking for internships with businesses and companies in the viticulture and winery industries during 2021. Please contact Danielle Buhrow, Senior Academic Advisor and Graduate Program Coordinator in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, for more information.

A recent donation of 40 acres near Willcox plus recent funding from the USDA-AZDA Specialty Crop Block Grant program are some of the first steps of a newly formed public-private collaboration towards a Viticulture Center of Research (VCOR) that will help support winegrape growing in Arizona. The funding will provide resources to convene the state viticulture industry and its supporters in the latter half of 2021 to determine common interests and develop plans for moving the VCOR project forward. Another first step is to gather letters of support that demonstrate backing of the VCOR project from the Arizona viticulture industry to relevant leaders in the University of Arizona. To learn more about the VCOR project and how to contribute a letter of support, please contact Joshua Sherman, commercial horticulture agent with University of Arizona Cooperative Extension.

For those of you in southeastern Arizona, Cooperative Extension manages an email listserv in coordination with the Tucson forecast office of the National Weather Service to provide information in the days leading up to agriculturally important events, like days with high winds or excessive heat. Please contact us if you'd like to sign up.

Please feel free to give us feedback on this issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter, suggestions on what to include more or less often, and ideas for new topics.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Please contact us to subscribe.

Have a wonderful May!

With support from: